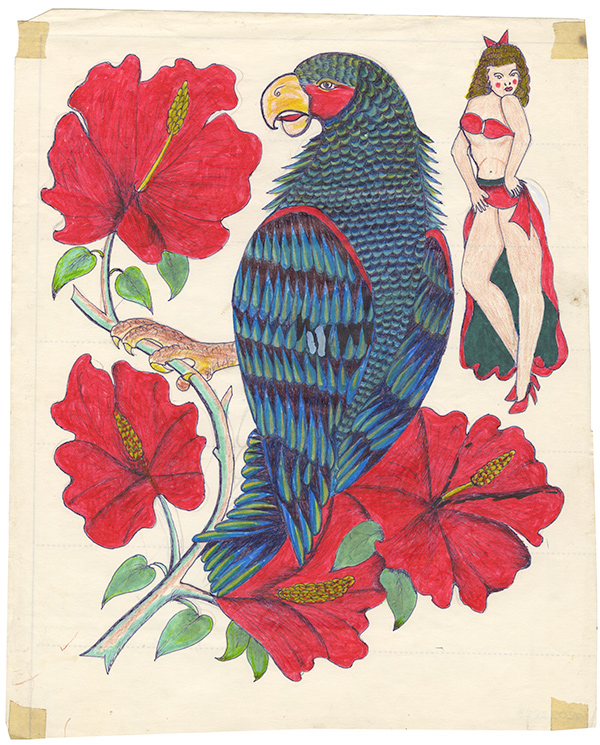

SEE RARE IMAGES FROM THE EARLY HISTORY OF TATTOOS IN AMERICA

time.com Olivia B. Waxman, February 28, 2017

Getting tattoos can be painful, but did you know they were partly invented to treat pain? In the mid-18th century, Native American women tattooed themselves to alleviate toothaches and arthritis, similar to acupuncture.

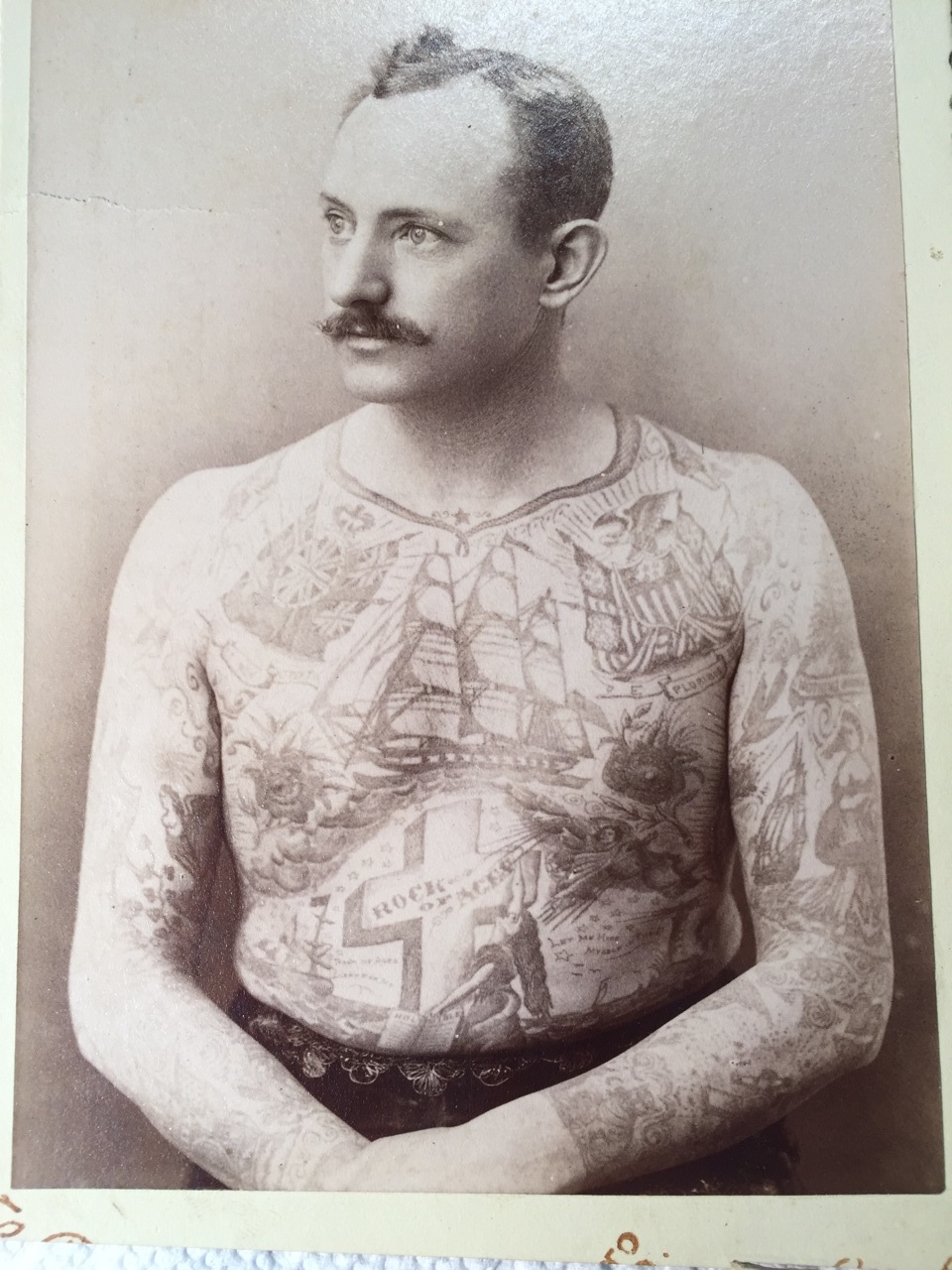

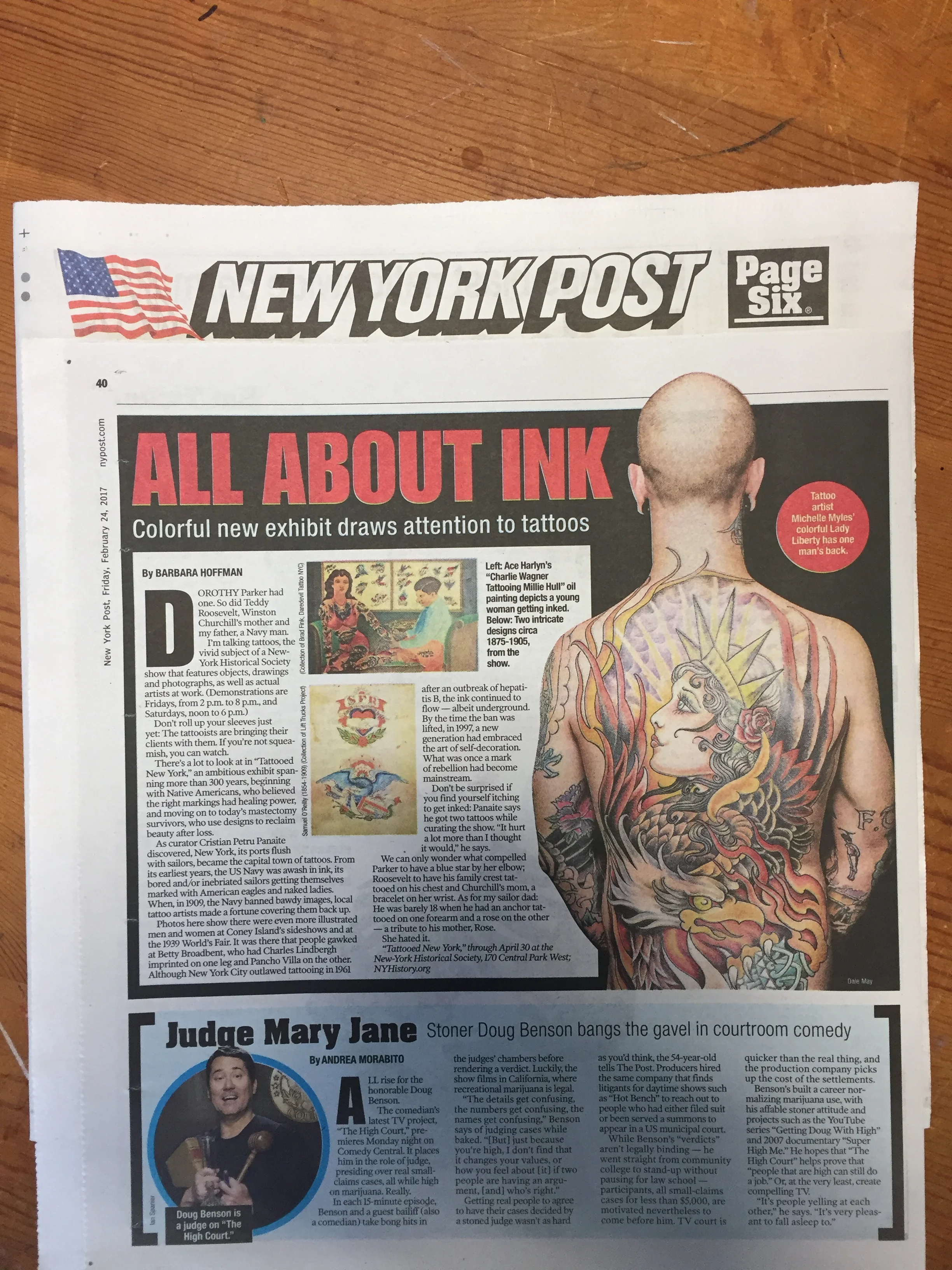

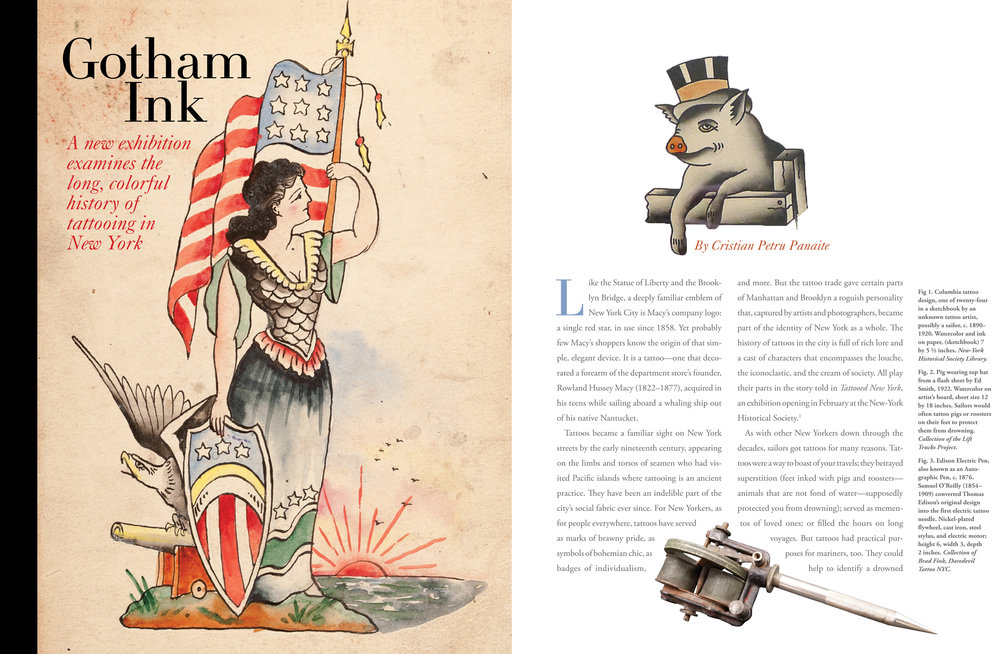

New York City is considered the birthplace of modern tattoos because it's where the first professional tattoo artist Martin Hildebrandt set up shop in the mid-19th century to tattoo Civil War soldiers for identification purposes, and it's where the first electric rotary tattoo machine was invented in 1891, inspired by Thomas Edison's electric pen. So it's fitting that the city is currently home to two separate exhibitions on the history of the art. Tattooed New York, from which the fact above is drawn, documents 300 years of tattooing at the New-York Historical Society. At the same time, with The Original Gus Wagner: The Maritime Roots of Modern Tattoo, the South Street Seaport Museum dives into the maritime origins of tattoos by showcasing the life of the sailor and sideshow star Gus Wagner, whose 800 tattoos earned him the title of the most tattooed man in America at one point and who was one of the first sailors to see that there was money to be made in tattooing.

In English, the word "tattoo" has late-16th century origins. Somewhat ironically, in the United States their history among indigenous peoples goes back even earlier than that — but, though the idea was already widespread on American soil, it would take voyages to the other side of the world to turn the tattoo into a mainstream American concept.

One of the earliest images of a tattooed person is of the King of the Maquas (the Mohawk tribe) whose chest and lower part of his face are covered in black lines, as seen in The Four Indian Kings, a portrait series painted when Mohawk and Mohican tribal king traveled to London in the early 18th century. Another is a 1706 pictograph by a Seneca trader that represents his signature tattoos — the one of a snake on his face and one with a bird, a symbol of freedom. At this point in American history, indigenous people often sported tattoos representing battle victories or protective spirits, of which the bird was one example, according to New-York Historical Society curator Cristian Petru Panaite (who sports a tattoo of his U.S. naturalization date).

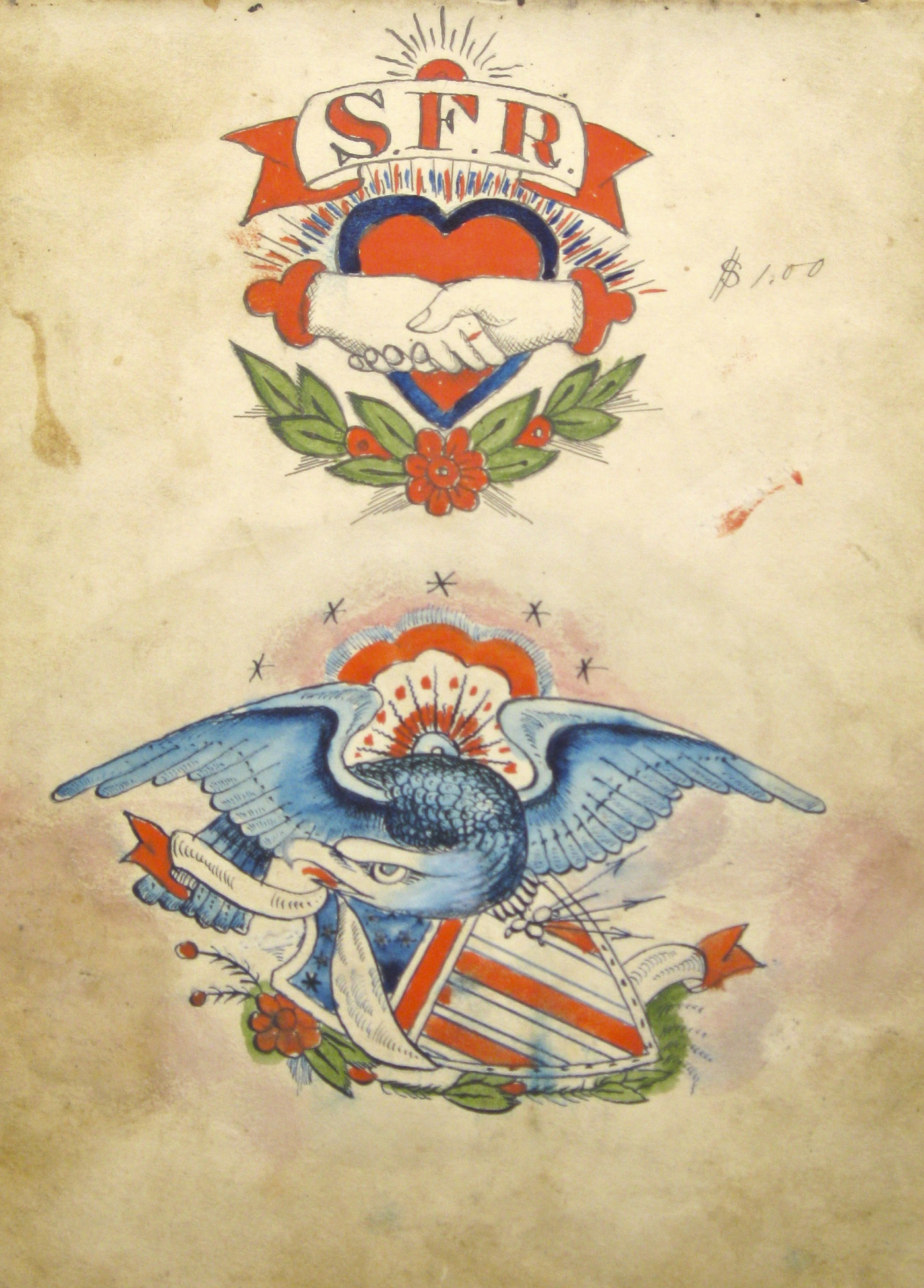

But it was during voyages to the South Pacific led by explorers like James Cook and William Bligh that Western sailors began to learn about traditional Polynesian pictographic tattoos. Before long, they were getting inked — sometimes with the name of a particular ship or their birthdates, or to mark the first time they crossed the equator or rounded Cape Horn or the Arctic Circle. (The word "tattoo" also comes from Polynesian sources.) The common anchor tattoo was meant to signify stability and to safeguard them from drowning, and is also thought that some got tattoos of pigs and roosters on their feet for the same reason because legend has it those animals rush to land. "Sailors are a superstitious lot," says Capt. Jonathan Boulware, executive director of the South Street Seaport Museum.

Eventually, the spread of tattooing among sailors led to the spread of the concept among landlubbers too.

"Tattooing in the U.S. started along the East Coast and West Coast and then worked its way inland," says Boulware, who points out that the same goes for " how any new thing came to any place" back then.

It was in the Victorian 19th century that they became a fashion statement for socialites — "a fashionable flirt with the exotic," as the N-YHS exhibit puts it. Ever conscious about what the British royalty were up to, New York's high society decided to get tattoos after hearing that Britain’s Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) had gotten body art during an 1862 trip to Jerusalem, while his sons Prince Albert and Prince George (future King George V) got dragons inked in Japan by Hori Chyo, an artist known as "the Shakespeare of tattooing.”

But, though the royals who set the trend were men, many of those who picked up the idea on the other side of the pond were women. These women wouldn't be seen at tattoo parlors; tattoo artists would make house calls. Ads would often characterize body art as costing as much as a fine dress but not as much as fine jewelry. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill's mother, Lady Randolph Churchill, had a snake tattoo on her wrist that could be hidden by bracelets when necessary. The New York World, reports the Historical Society, placed the percentage of fashionable NYC ladies who were inked at the turn of the century around three-quarters. Trendy designs of the time included butterflies, flowers and dragons.

Nor were those socialites the only women getting tattoos. In the mid-19th century and the early 20th century, women who flaunted their colorful body art could make a living at circuses or sideshows. And, though those shows got a bad reputation for exploiting women, who did often participate in strip-teases to show up their ink, Panaite argues that they actually offered women a rare opportunity for economic independence and fame at a time when job opportunities were limited. (The exhibit points to Betty Broadbent, one of the 20th century’s most photographed tattooed women, as an example of this phenomenon.) Though many early sideshow performers told stories about how their tattoos had been forced upon them during kidnappings — for example, one Nora Hildebrandt said that she had been kidnapped by Native Americans during a journey West and tattooed against her will — those stories were eventually replaced with narratives of the women's personal liberation and freedom.

"These are women who were business-savvy, who learned how to make a living and profit by capitalizing on this fascination with tattoos," says Panaite. "Tattoos were an early way that women took control of their bodies.”

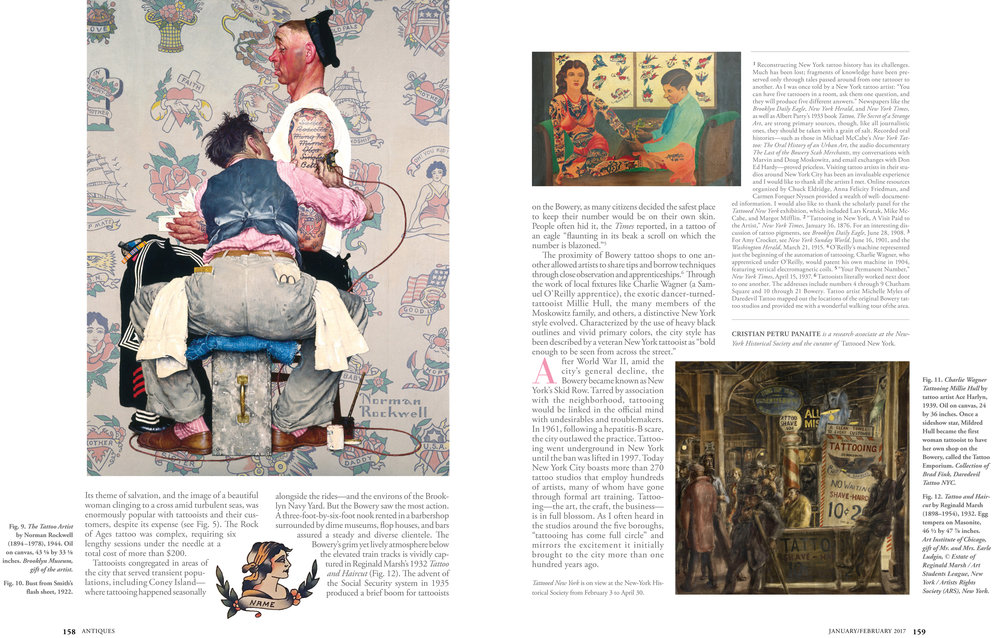

Many of these colorful women were still being tattooed by male artists, but Mildred Hull (who boasted 12 tattoos of geishas on her legs and 14 of angels on her back) is considered the first woman to open a tattoo shop on the Bowery, in the back of a barbershop. And then there were the tattoos that were truly mainstream: In the 1930s, when Social Security numbers were introduced, people flocked to tattoo parlors to get their numbers inscribed on their arms, chests or backs as a memory aide.

In the mid-20th century, even as musicians like the Grateful Dead and Janis Joplin helped make tattoos even cooler, the form suffered a setback in the city, as a 1961 hepatitis outbreak blamed on a Coney Island tattoo artist had prompted the New York City health department to ban tattooing. At a time when tattoos were seen as signs of promiscuity, Ruth Marten, a tattoo artist during the 1970s, says many of her clients were women getting a divorce, including one who told her that she "wanted to be able to change her body to something that her ex-husband had had no experience with." Some tattoo artists moved their offices out of the city, while some just worked out of their apartments until Mayor Rudolph Giuliani lifted the ban in 1997.

And since then, that history continues to evolve, as tattoos have gotten even more common.

"So many people are getting tattoos," says Panaite, "that we will have some really cool retirement houses."