The New-York Historical Society explores three centuries of Gotham’s relationship to the tattoo through vintage images, electric pens, and live demonstrations.

ALLISON MEIER, APRIL 6, 2017, hyperallergenic.com

Tattooing in New York has been a sideshow attraction, a banned underground practice, and an elite society trend. Performers in the early 1900s Bowery dime museums boasted wild tales of forced tattoos at the hands of “Indians,” while in the late 19th century, they were a fad with fashionable ladies, who got Japanese-style dragons and flowers inked in discreet places. Thomas Edison pioneered an electric pen in 1875, supposedly trying out some dots on himself in the process (although it was intended for reproducing documents). Then, just under a century later, in 1961, the city’s health department declared that it was “unlawful for any person to tattoo a human being.” The rule referenced several cases of Hepatitis B, but was likely meant to smooth the city’s rough edges ahead of the 1964 World’s Fair — never mind that the fully tattooed Betty Broadbent had been a star in the beauty pageant of the 1939 World’s Fair. Tattooed New York at the New-York Historical Society explored this complex history chronologically, emphasizing Gotham’s centrality in the development of the medium.

The exhibition, organized by Assistant Curator of Exhibitions Cristian Petru Panaite, opens with the indigenous tattoo traditions of New York, visualized through a group of 1710 mezzotints called “The Four Indian Kings.” Created by British printmaker John Simon after the work of John Verelst, they depict three Mohawk and one Mohican who went to London to ask for support for their tribe’s interests. The emissaries were treated more as a cultural sensation than a persuasive political force, unfortunately, and Simon’s prints were one of many responses to their unfamiliar appearance, including their tattoos. While I would have loved to learn more about the practice in the 18th-century United States, Tattooed New York then leaps offshore to the sea, where bored 19th-century sailors inked each other with good luck charms and scantily clad ladies. When they returned to ports like New York, they sometimes displayed their tattoos for money, or even set up shop.

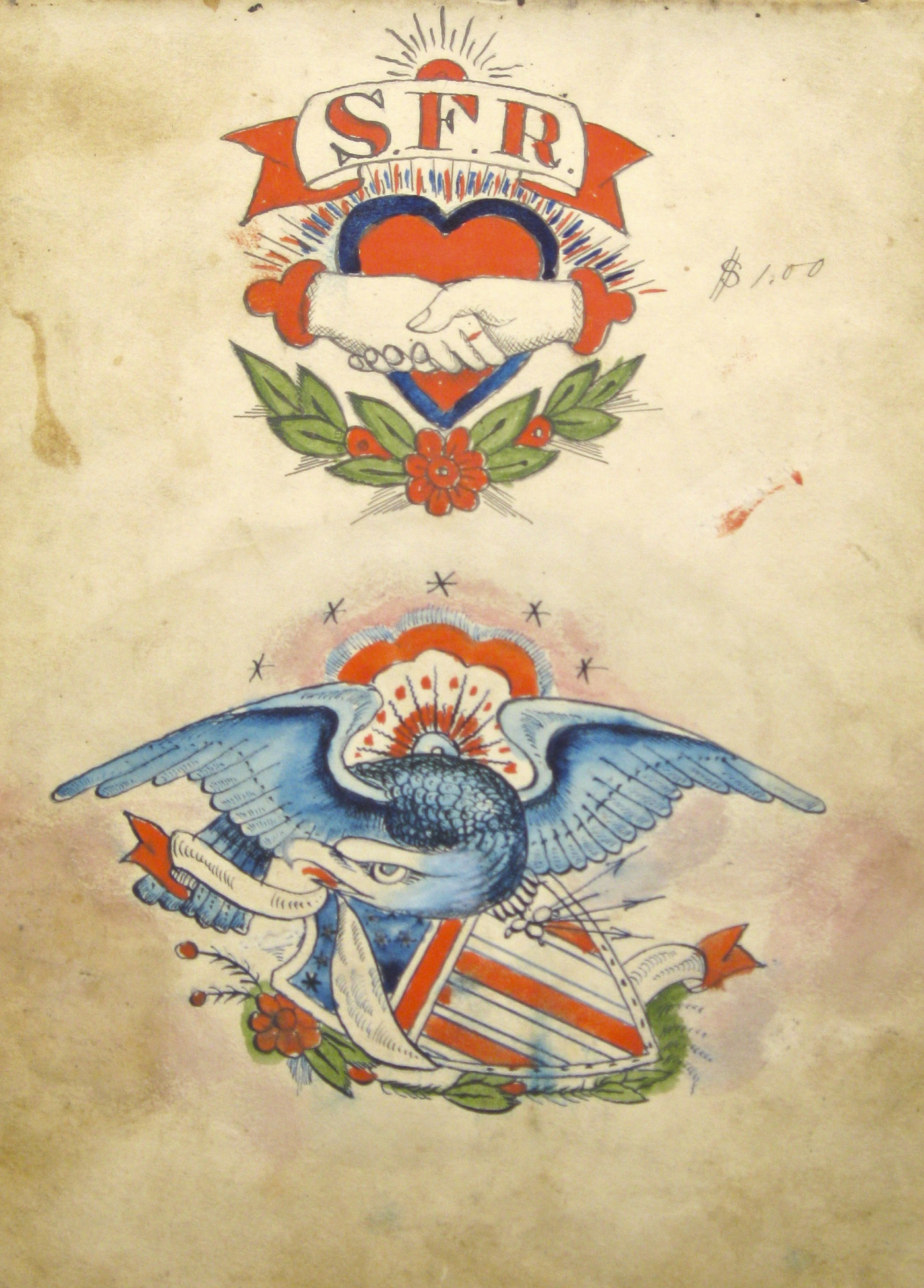

Later, in the Civil War era, tattoos became popular with soldiers as a way of posthumous identification, a practice taken up by the New York–based Martin Hildebrandt. (He went on to ink Nora Hildebrandt, believed to be the first professional tattooed woman.) After Tattooed New York reaches the turn of the 20th century, its timeline gets tighter, and the individual characters that propelled the art, more distinct. Some tattoo artists, such as Samuel O’Reilly, inventor of the electric rotary pen and the first to open a mechanized tattoo shop in 1898, concentrated around the Bowery, while others gathered in Coney Island. Japanese artists arriving in the city introduced new inks and styles, with rice paper stencils giving way to acetate in the early 1900s. Sometimes a phonograph needle was used to trace a pattern, until the photocopier emerged in the 1980s.

Many of the early artists and their customers were men, yet Tattooed New York includes a series of cabinet cards of influential tattooed ladies. Some, including Irene Woodward, who had over 400 designs on her skin, told elaborate stories of being forcibly inked “by Indians” — a mythical story that went back to the 1850s and Olive Oatman, whose face tattoos, a mark of her status among the Mohave people, were sensationalized. Other women were tattoo artists themselves, like Trixie Richardson, who gave thousands of 1920s women their own subtle butterflies and forget-me-nots.

The 1961 tattoo ban, which endured until 1997, sent the parlors underground. On view is a 1962 window shade of flash designs from Tony D’Annessa’s tattoo shop on West 48th Street; he could quickly pull it up, as if he were the owner of a Prohibition speakeasy hiding its booze. During the time of the ban, tattoos also paradoxically started to get mainstream appreciation, appearing in exhibitions and supporting the public’s fascination with the art.

That fascination continues: at this moment, New York is flush with vintage tattoo exhibitions. The South Street Seaport Museum is tracing the “maritime roots of modern tattoo” through the early 20th-century work of Gus Wagner, and Ricco Maresca Gallery is exhibiting the midcentury tattoo art of Rosie Camanga, who moved from the Philippines to Honolulu right before World War II. Tattooing, of course, reaches far beyond New York; even Ötzi the Iceman, who died somewhere around 3105 BCE, has tattoos. But Tattooed New York demonstrates how the city’s legacy of international exchange and constant possibilities for self-metamorphosis have generated a unique style and tattoo culture. Fittingly, the exhibition’s three centuries of history culminate with contemporary art installed in a gallery that hosts live tattoo demonstrations on selected Fridays and weekends (the schedule is available online). There, visitors can witness the transformation of skin into canvas.

Samuel O’Reilly, “Eagle and shield” (1875–1905), watercolor, ink, and pencil on paper (collection of Lift Trucks Project)

Irving Herzberg, “Tattoo shop of ‘Coney Island Freddie’ just prior to New York City’s ban on tattooing” (1961), digital print (courtesy Brooklyn Public Library)