All the mainstream U.S. media are terrified to publish this cartoons. Editors are hiding under their desks at The Associated Press, CNN, the New York Times, MSNBC, NBC News and others .

Other media outlets like Gawker, the Daily Beast and BuzzFeed have all published the images. The Washington Post ran the cartoon on their editorial opinion page.

The New York Times proffered one of their typical gasbag explanations: “Under Times standards, we do not normally publish images or other material deliberately intended to offend religious sensibilities. After careful consideration, Times editors decided that describing the cartoons in question would give readers sufficient information to understand today’s story.”

Kind of like describing a sunset or texting what a celebrity looks like?

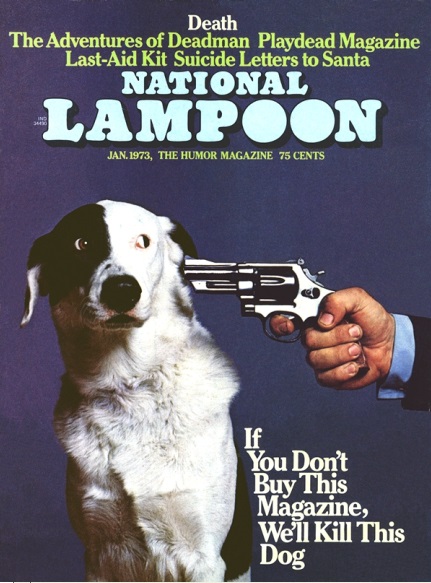

Look, it's not a really good cartoon, it's not particularly well drawn, not really that funny.

A far cry from this classic.

But it's news. It probably says something like: 100 lashes if you don't think this is funny.

A Close Call on Publication of Charlie Hebdo Cartoons

JANUARY 8, 2015 2:18 PM January 8, 2015 2:18 pm

Was The Times cowardly and lacking in journalistic solidarity when it decided not to publish the images from the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo that precipitated the execution of French journalists?

Some readers I’ve heard from certainly think so. Evan Levine of New York City wrote: “I just wanted to register my extreme disappointment at what can only be described as a dereliction of leadership and responsibility by the New York Times in deciding not to publish the Charlie Hebdo cartoons after today’s massacre.”

Todd Stuart of Key West, Fla., expressed the same view: “I hope the public editor looks into the incredibly cowardly decision of the NYT not to publish the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. I can’t think of anything more important than major papers like the NYT standing up for the most basic principles of freedom.”

And many outside commenters and press critics agreed. Jeff Jarvis of City University of New York wrote: “If you’re the paper of record, if you’re the highest exemplar of American journalism, if you expect others to stand by your journalists when they are threatened, if you respect your audience to make up its own mind, then dammit stand by Charlie Hebdo and inform your public. Run the cartoons.”

I talked to the executive editor, Dean Baquet, on Thursday morning about his decision not to show the images of the prophet Muhammad – a position that was taken by The Washington Post (on its news pages), The Associated Press, CNN and many other American news organizations. BuzzFeed and theHuffington Post were among those that did publish the cartoons.

The Washington Post’s editorial page published a single image of a Charlie Hebdo cover on its printed Op-Ed page with Charles Lane’s column; that decision was made by the editorial page editor, not the executive editor of the paper, who presides over the news content. The executive editor, Martin Baron, told the Post’s media reporter Paul Farhi that the paper doesn’t publish material “that is pointedly, deliberately, or needlessly offensive to members of religious groups.”

A number of European newspapers did publish the images, often on their front pages or prominently on their websites.

I found it interesting that at least one outspoken champion of free expression, Glenn Greenwald, questioned the solidarity angle, tweeting: “When did it become true that to defend someone’s free speech rights, one has to publish & even embrace their ideas? That apply in all cases?”

And even many people who were horrified by the attack have become troubled by the embrace of a paper they believe crossed the line into bigotry.

Mr. Baquet told me that he started out the day Wednesday convinced that The Times should publish the images, both because of their newsworthiness and out of a sense of solidarity with the slain journalists and the right of free expression.

He said he had spent “about half of my day” on the question, seeking out the views of senior editors and reaching out to reporters and editors in some of The Times’s international bureaus. They told him they would not feel endangered if The Times reproduced the images, he told me, but he remained concerned about staff safety.

“I sought out a lot of views, and I changed my mind twice,” he said. “It had to be my decision alone.”

Ultimately, he decided against it, he said, because he had to consider foremost the sensibilities of Times readers, especially its Muslim readers. To many of them, he said, depictions of the prophet Muhammad are sacrilegious; those that are meant to mock even more so. “We have a standard that is long held and that serves us well: that there is a line between gratuitous insult and satire. Most of these are gratuitous insult.”

“At what point does news value override our standards?” Mr. Baquet asked. “You would have to show the most incendiary images” from the newspaper; and that was something he deemed unacceptable.

I asked Mr. Baquet about a different approach — something much more moderate, along the lines of what the Post’s Op-Ed page did in print.

“Something like that is probably so compromised as to become meaningless,” he responded, though he was speaking generally, not of The Post’s decision.

The Times undoubtedly made a careful and conscientious decision in keeping with its standards. However, given these events — and an overarching story that is far from over — a review and reconsideration of those standards may be in order in the days ahead.