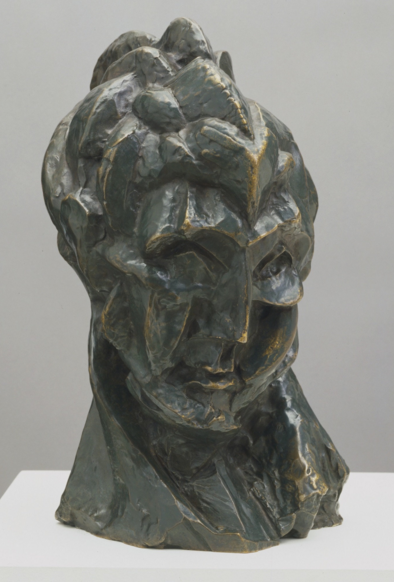

Woman’s Head (Fernande) 1909, Bronze

To attend the Picasso Sculpture Exhibit at MoMA is to witness the secret workings of a relentless creative mind. Never schooled in sculpture, he was free to explore its potential, without fear of failure. Coupled with his sense of playfulness and rebellious outlook, he worked in the gap between painting and sculpture. He made no assumptions about what a sculpture could be, and he didn’t let convention get in his way. Richard Serra said, “Picasso seems to be actually more inventive in sculpture than in painting.” What few realize is that the greatest painter of the 20th century was also the greatest sculptor of the 20th century. To see this show is to know the canon other serious sculptors must compare themselves.

Picasso once famously said, “Good artists borrow, great artists steal.” and the artist he stole the most from was Cezanne, a painter who not only painted what he saw, he painted how he saw. Cezanne eschewed staining, “sculpting” his work with thick brushstrokes, and with multiple perspectives, he reduced his pictorial elements to cubes, cones, and cylinders. From this starting point, Picasso created Analytical Cubism. Picasso took Cezanne at his word, and he painted cubes that fractured the picture plane, creating a breathing space for shapes to float in and out. Facilitated by the freedom this structure offered him, he investigated multiple views of perception. Picasso painted some of his most provocative works of art at this time, and propitiously, he continued to work in sculpture.

The first room in the show shows how quickly Picasso progressed in his early 1903 to 1909 period. From a sentimental bust of a bronze harlequin to a primitive wood sculpture of a nude, you are immediately led to his breakthrough work, Woman’s Head 1909. Modeled out of clay, and then cast in bronze, Woman’s Head, portrays his lover, Fernande, from multiple viewpoints, as partly buried cubes emerge from a block of clay. Picasso tries to release his cubes and make them float, but traditional sculptural processes hold him back. Unlike his paintings, there isn’t any air in this work, which limited his potential for spatial exploration. Multiple viewpoints stuck in the mud of the clay, lack clarification. Luckily, his painting process offered a solution to his predicament.

Still life with Guitar. Variant state Paris, assembled before November 15, 1913, Subsequently preserved by the artist Paperboard, paper, string, and painted wire installed with cut cardboard box

While working on his still life paintings, Picasso would use sketches, or maquettes, as the reference for his work. One of these sketches was a three-dimensional cutout of a guitar, handmade of paperboard, paper, string and painted wire, glued together. A photo of it exists as a centerpiece in a three-dimensional tableau made of paper cutouts. Once finished, Picasso had an insight. Why couldn’t the sketch stand alone and be the sculpture? That way, it would free up the negative space of his work allowing shapes to float, as they did in his paintings, allowing multiple viewpoints to mesh with each other. This bold move demonstrated a rejection of the lofty subject matter of sculpture. This wasn’t a statue of a goddess, a general on a horse, or even his mistress. It was a sculpture of an inanimate object. Of a guitar! Then in 1916, Picasso folded up the paper guitar and put it away in a box. It remained there for 64 years until the MoMA acquired and displayed it again, soon after the artist’s death. Fortunately, before mothballing the paper sculpture, Picasso decided to make a more permanent version of it in 1914.

Guitar, Paris, after mid-January 1914 Ferrous sheet metal and wire

Guitar 1914 wasn’t made from clay, wood, or marble. It was made with metal. It wasn’t carved, chiseled, or molded. It was constructed. It even had lines (the strings were made of wires). It hung on a wall. What was it then? With Guitar, Picasso resolved a conflict between painting and sculpture by introducing a strange hybrid. Some called it pictorial sculpture.

Here, Picasso answers ‘why’ questions. Why is sculpture always about the human form, when it could be of an inanimate object? Why can’t it be assembled, when you can construct it out of metal? Why does it have to be on a pedestal, when it can hang on a wall? Why does sculpture have to be so serious, when it could be fun? By challenging sculpture’s very nature, Picasso brought a new energy to the medium. The poet Andre Salmon observed, “We were delivered from painting and sculpture, liberated from the imbecilic tyranny of genres.” Guitar 1914 set the stage for the greatest sculptural exploration and innovation of the 20th century.

Still Life, 1914, painted pine and poplar, nails, and upholstery fringe. About 12 inches high.

Still Life, 1914 is the first sculpture that made fun of sculpture. Instead of carving, he paints pine and poplar wood and nails them together. Although still life as a genre is within the purview of painting, Picasso boldly makes it the subject of sculpture. By portraying a workman’s lunch, he offers a sardonic commentary on the ‘high’ ambitions of ‘Art’. (A Dutch Master, 17th century feast, it isn’t.) Haphazard sawn wood, machined and hand carved, refute the journeyman’s aesthetic of refinement. Further blending painting and sculpture, he uses paint to distinguish the surface of the glass (glossy) and the rest of the tableaux (matte). The addition of tasseled upholstery fringe, a found object integrated into the piece, proffers another snub at the craftsmanship, giving the piece an air of insouciance and whimsy. This daring act, incorporating real objects into sculpture, unleashed a creative fervor that resonates to this day. But this is just the beginning for Picasso, and there are so many more rooms to go through.

Pablo Picasso. Figure. 1928

Picasso’s quest to have his sculpture breathe led to another breakthrough, Figure, 1928, a rejected study for the tomb of his friend Apollinaire. Once again, a painter’s perspective creates a new sculptural form, but, this time, using Surrealist imagery. Inspired by the strings in his guitar sculptures, he created a piece made entirely of welded wire. A contemporary art dealer declared it ‘drawing in space.' Sculpture as drawing, freed up the medium, allowing new avenues of creativity by using line and air for expression. Once again, Picasso’s disregard for the status quo showed the way for artists to use unorthodox materials and techniques.

Picasso's 'Bull's Head' Paris, spring 1942 Bronze, cast in 1943

Assembled out of a bicycle seat and handlebars, Bull’s Head evokes a smile. Bold simplicity and a good coupling of two disparate bicycle parts surprise with a depiction of a bull. But then, Picasso takes it a further step, as he casts the assemblage. Now, Picasso comes full circle with another desecration. After embracing the commonplace by incorporating it into his art, he now sanctifies it with bronze. The 19th century must have been rolling in its grave.

Chair Cannes, 1961. Painted sheet metal, Musée National Picasso–Paris.

What Figure 1928 did for the line, Chair Cannes did for shape. This kooky sculpture questioned the fundamental processes of its medium. First cut out of paper, folded, and then flattened out (at this stage Picasso said it looked like a chair run over by a steamroller), craftsmen then bent a single sheet of painted metal, based on the paper template, to create an art object. Made of only one part, he manipulated the material of the work itself, to create a complex piece without soldering or welding. Only gravity holds it together. Bent and turned planes create their own negative space. With a mundane object as subject and a simple shape as a sculptural form, with bending as process and gravity as glue, Guitar Cannes, advanced both the mental and visual gymnastics of Picasso’s art – not bad for an 80-year-old.

To tour this show is to explore the creative mind. How are new ideas formed? How does one find the confidence and courage to embrace them? Picasso shows the way with his unrelenting curiosity, reassessment of assumptions, and rejection of category norms. He asks big questions by challenging the opposing prejudices of painting and sculpture. His nonchalance enabled risk taking, with a take-or-leave-it attitude. What is the secret to Picasso’s prolific creativity? He had fun.

Thomas McManus is a writer, artist and professor at Fashion Institute of Technology in NYC.